For anyone studying or interested in mechanical engineering and related research and development, working with an Artec 3D scanner is a revelation. One doesn’t fully appreciate its possibilities until working with it in earnest. For example, one can reverse engineer a component – say a six-cylinder engine block – by scanning it, cleaning up the data, creating a point cloud, and then exporting the point cloud to a CAD program. As a result, a workable model is obtained with a reasonable dimensional accuracy within hours, as opposed to modeling based on manual measuring or in a coordinate measuring machine (CMM). A process one might have to do several times, taking significantly longer.

This is just one use for the technology. One could also set up virtual reality environments that are in scale with photo-realistic textures. One is able capture data from anywhere and use it in reverse engineering, training simulators for A.I, robots, etc. If all of this sounds a bit too good to be true, well, that is because it is, kind of.

Scanning a hockey player

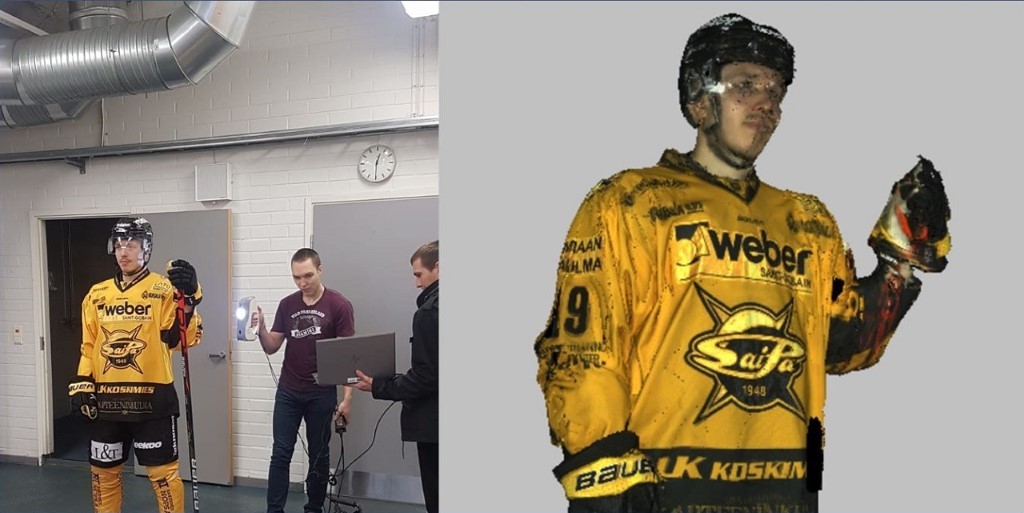

The technology has all the capabilities mentioned and likely uses that have not been thought of. Not to mention the software, which has not even been touched upon. Still, there is a “but.” The process has a steep learning curve. A LAB University of Applied Sciences project team was assigned to a project commissioned by a local company, Sunrob, who have an interest in providing large scale 3D printing services, and SaiPa, who were interested in creating a scale model of a hockey player for marketing purposes (figure 1).

Scanning people is not the ideal use case for a 3D scanner. People breathe, fidget, and in general, are not particularly good at standing stock still for 10 minutes. The physical task of going around a larger, moving object and scanning it section by section can be tricky. Luckily, the algorithm in the Artec Studio can provide amazing results even with poor-quality raw scan data.

What at first looks like a mess of geometry can within hours of work become a photorealistic representation of a person (figure 2). As the hardware is relatively simple to use, a large part of the time was spent learning how to move with the scanner: keeping the right distance without losing track of the object being focused on and keeping an eye on the laptop showing what the scanner sees. Getting more efficient at this and the software has been gratifying.

All in all, 3D scanning could be described as art even if the end is engineering, combining the best of both technical and imaginative work.

Authors

Rigo Kendrali is student assistant in LAB Laboratories of technology in Lappeenranta campus where the main task has been to investigate the possibilities of the 3D scanning in human scanning.

Eero Scherman is Development engineer in LAB Laboratories of technology in Lappeenranta campus. In this project the main tasks have been to coordinate the co-operation between LAB UAS and the participating companies as well as providing technical guidance for the 3D-scanning.

Links

Artec Europe. 2021. Scanners. Eva. Accessed 13.1.2021. Available: https://www.artec3d.com/portable-3d-scanners/artec-eva-v2